In Colombia, renewable energy technologies are recently implemented. Although wind energy’s execution started more than 20 years ago in industrialized countries, here is part of a new scene in which public and private entities’ efforts are directed towards energy transition. On paper, only 0.1% of the energy transformed in the country comes from one wind park; however, at the moment I write this, that system is not in operation. This allows the classification of wind power as an emerging technology in this country.

In the process of implementing new technologies, it is necessary to apply an approach for their ethical study. Ethical studies consider moral mediation of technologies, and they aim to reflect on their possible consequences considering various ethical principles and levels of analysis, which yield relevant insights to contemplate at the moment of implementation. There are several methods to perform ethical studies, one of them is called Anticipatory Technology Ethics (ATE), and its methodology is partially applied in the following reflections.

ATE methodology can be applied to “contemporary and future emerging technologies” and it defines the objects of ethical analysis based on technology, artifacts, and application levels. In this case, the ethical analysis focus is the concrete application of Eolic turbines as energy transformation artifacts, belonging to wind technology.

Eolic turbines are gigantic apparatuses that transform the kinetic energy of wind when it moves them to electrical energy. They can be up to 160 meters tall, the blades up to 80 meters in length, although exist developments of turbines with blades of 118 meters [3]. These wind power systems can be installed onshore and offshore. As a new technology in Colombia, there are ethical points that must be considered in the implementation to avoid heavy consequences in the habitat, people, and everything else around them.

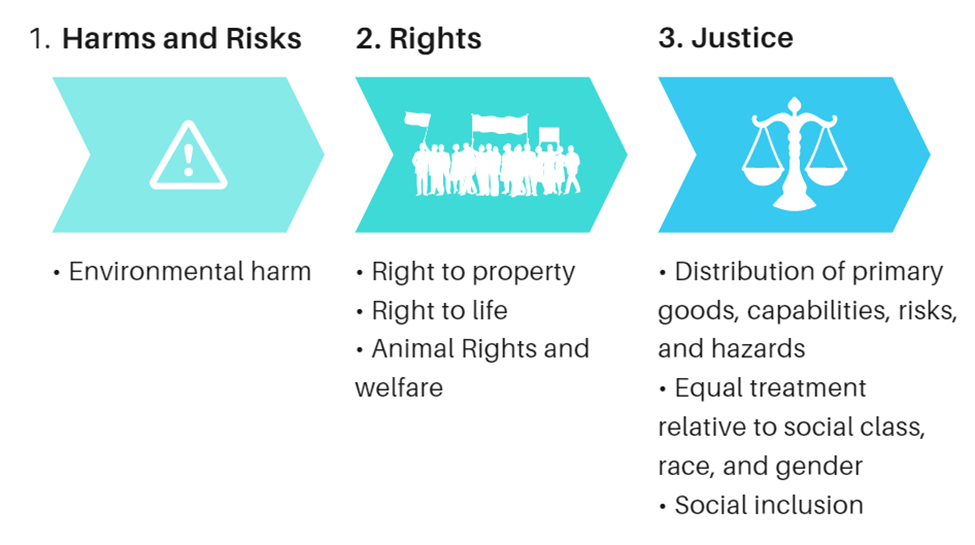

Thus, to analyze the ethical issues that this technology may present at the application level, the ATE approach suggests their division into three groups. The first one covers “moral issues relating to the intended use of the artifact”, the second one consists of “moral issues concerning side-effects or unintended consequences for users”, and the third one consists of “moral issues pertaining the rights and interests of non-user stakeholders who may be affected by a particular use of the artifact”. The latter are the kind of issues that will be discussed here.

The ATE and other ethical studies methods propose the definition of a checklist to identify the areas of analysis. Bellow, it is found a list I selected to analyze the ethical implications that wind turbines used for energy transformation could carry out. In addition, the selected areas are evaluated considering that the wind power artifacts mediation is contextual, in a way in which they do not influence human behavior directly but shape the environment in which are installed.

The harms and risks related to the implementation of wind power systems can affect the environment. Both in onshore and offshore installations require a noteworthy amount of area and, in case of the latter, the ocean ecosystem is intervened with machines to gather “information […] on the properties of the seabed to properly select and design foundations, determine installation requirements, and predict the short and long-term performance of […] support structures”, which could lead to damage of the marine fauna and flora and also implicate endanger animal rights and welfare.

In addition, the property right is relevant when we talk about a technology application that requires extended areas of soil. In the Colombian context, the legal and illegal control of territories usually results in the forced displacement of people in rural zones. Then, wind power systems could indirectly intimidate people to leave their homes and go to other places, also affecting their right to a dignified life. Wrongly managed, the soil used for these kinds of projects could lead to forced displacement like has happened before with hydroelectric energy systems installed in the country.

Concerning justice matters, wind turbines could, paradoxically, mediate an unfair distribution of goods like energy. Although the only wind park in the country, which is located in La Guajira, the 4th department with the higher multidimensional poverty in the country, is not working now, it operated for more than 10 years in which did not contribute “a single kilowatt of energy for the benefit of the community”.

Additionally, the local communities of the installation places usually belong to a vulnerable population and could be treated unequally due to their social class, race, and/or gender, and even be tricked, considering their lack of information and tools to defend their collective rights. An analysis of the development of the wind park in La Guajira mentions that “the lack of knowledge on this issue was due to the absence of training and information on the part of the State, […] in addition to having unpleasant experiences with multinational companies that do not have a responsible practice in their projects.”. The latter point also reflects the effects of the cultural differences between the rural inhabitants, the technology pretended to install, and the people behind it.

In conclusion, although wind turbines are artifacts that only establish a background relation with people and they have a promising potential to tackle the energy transition we urgently need, there are ethical considerations behind them that are compulsory for their implementation. Environmental harm and possible endangerment of rights and social justice for the population in the rural areas, where the wind power systems are located, are necessary points for a responsibility assignment stage, in which different actors, like private companies and the government, act to implement the technology ethically.

Leave a Reply